More than 5,000 women in Thailand die every year from cervical cancer [1], according to the 2019 report from the HPV Information Centre. 70% of these cancers are caused by just two human papillomavirus (HPV) strains: HPV16 and HPV18. Both of these strains are now vaccine-preventable, but the HPV Information Centre estimates that it will take decades before the vaccine’s full impact is felt. Furthermore, as the vaccine cannot prevent all HPV infections or cancers, women will still need to rely on regular screening for early diagnosis of cervical cancer.

Currently, women are offered screening with a test that has been used for the last 70 years. Developed by Dr George Nicholas Papanicolaou, the eponymous Pap smear has been the gold standard screening tool to detect abnormal squamous cells in the cervix, a precursor to cancer. But with a sensitivity of just over 55% [2], and newer, more sensitive screening tools available, is it time to retire this old approach?

Since the inception of the Pap smear, our understanding of cervical cancer has advanced dramatically. We now know that HPV branches into two families— high-risk viruses including HPV16 and 18, as well as less common strains such as 31, 33, 45, 52, 58, and a few others [3], and low-risk strains, such as HPV6 and 11, which account for about 90 percent of genital warts, but rarely develop into cancer [3]. Pap smears do not distinguish between these two types. This inability to distinguish between malignant and benign abnormalities triggers a cascade of further investigations, many of which are unnecessary and cause needless anxiety for women.

But all this is changing. In 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first HPV test [4] for cervical cancer screening. This DNA-based test successfully detects the presence of high-risk HPV viruses at sensitivity levels of more than 94 percent [2].

What is equally important is the high confidence of a negative test result. Results from a 2009 study in India showed that no woman with an HPV negative result died of cervical cancer during the eight-year study period [5]. Further studies similarly reported the safety of a negative high-risk HPV test result over three years.

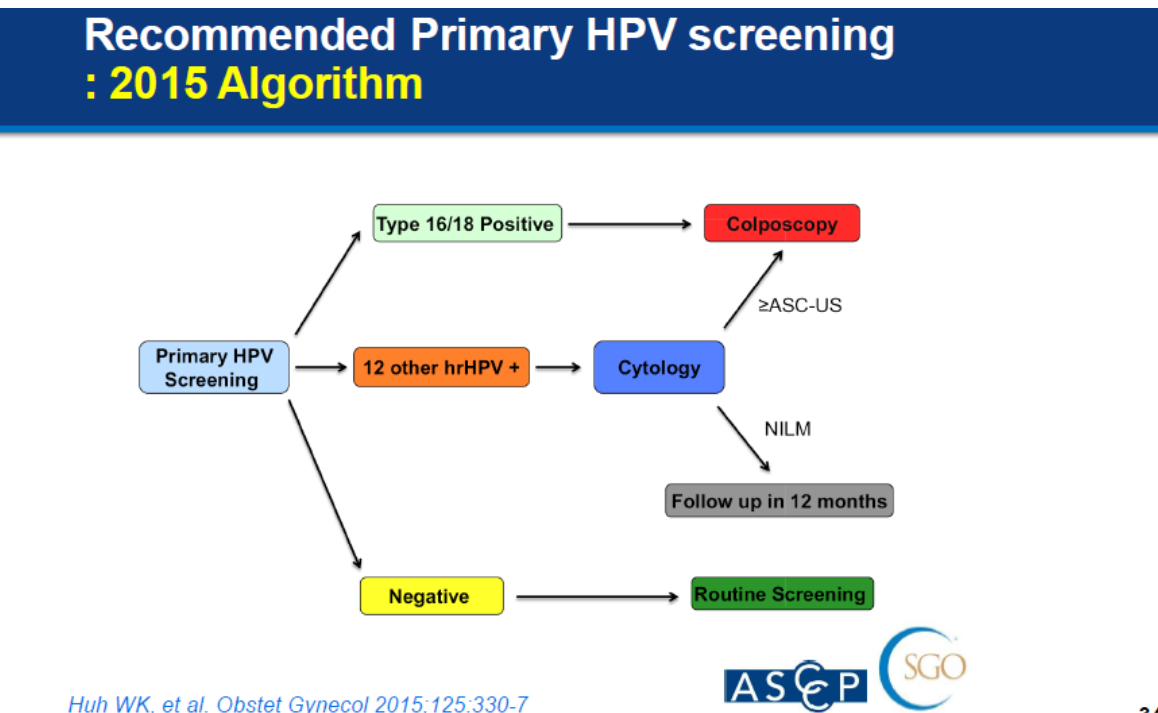

In 2015, the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) issued a new screening algorithm. By using high-risk HPV testing as a first-line screening tool, the Society argues, follow-up can be tailored to individual women’s needs, thereby eliminating unnecessary testing and enabling laboratory medicine services to deliver timely, value-added and focused screening programmes. Turkey, the Netherlands and Australia were the first to implement changes to their screening programmes.

In Thailand, the Thai Gynecologic Cancer Society embarked on a pilot project to evaluate a similar screening algorithm in 2016. It adapted the ASCCP algorithm to further distinguish between other high-risk HPV strains and modified the recommended intervals for routine screening to every three years.

To determine the cost-effectiveness of such as screening programme, we mathematically modelled three different screening approaches: Pap smear, high-risk HPV testing and focused HPV16/18 genotyping [6]. We concluded that high-risk HPV testing is the most cost-effective screening tool. HPV testing is cheaper than cytology and detects more early-stage cervical cancers than cytology alone.

As cervical cancer screening rates in Thailand remain suboptimal at only 50 per cent, colleagues at Chulalongkorn University reviewed the accuracy of results obtained by self-sampling at home, which is comparable to that obtained self-sampling at home, which is comparable to that obtained when sampling is performed by a physician or healthcare professional [7]. Self-sampling may help to further drive uptake of screening.

Primary screening with a DNA HPV test is a cost-effective strategy for Thailand that will enable early detection of cervical pre-cancers and cancers in more women and ultimately avoid unnecessary deaths from this disease.

References:

[1] Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases Report. HPV Information Centre

[2] Pap Smear vs. HPV Screening Tests for Cervical Cancer

[3] HPV/Genital Warts

[4] FDA approves first human papillomavirus test for primary cervical cancer screening; US Food and Drug Administration

[5] Sankaranarayanan, R., et al., 2009. HPV Screening for Cervical Cancer in Rural India. New England Journal of Medicine, 361(3), pp.304-306.

[6] Termrungruanglert, W., et al., 2017. Cost-effectiveness analysis study of HPV testing as a primary cervical cancer screening in Thailand. Gynecologic oncology reports, 22, pp.58–63.

[7] Nilyanimit, P., et al., 2014. Comparison of Detection Sensitivity for Human Papillomavirus between Self-collected Vaginal Swabs and Physician-collected Cervical Swabs by Electrochemical DNA Chip. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 15(24), pp.10809-10812.