Point-of-care coordination is an emerging career that focuses on implementing point-of-care testing (POCT) solutions across a wide range of hospital and healthcare settings, such as emergency departments, intensive care units, primary care clinics and paramedical vehicles. While still relatively new in the Asia Pacific region, a growing number of healthcare providers are hiring dedicated professionals to manage their POCT portfolios.

The role of point-of-care coordinators involves a variety of responsibilities, from evaluation and procurement of new tests to training POCT operators and ensuring that tests are used in accordance with all quality and compliance standards. These responsibilities require both analytical and leadership skills, as well as a familiarity with the full array of POCT technologies and an ability to navigate the complex organisational structure of hospital and healthcare systems.

Subscribe to LabInsights’ latest news and update

Join over 3,000 HCPs receiving insights in their inbox every week.

Thank you.

You have successfully subscribes to the newsletter!

Didn’t receive the email? Be sure to check your spam folder too!

You can contact [email protected] for further assistance

Alternatively, you can browse more content from ThoughtLeadership

In the Asia Pacific region, healthcare systems in both advanced countries and low-resource settings are taking interest in hiring point-of-care coordinators. This article draws on interviews with several POCT experts to understand the changing role of point-of-care coordinators in the region and the career opportunities it presents for laboratory and healthcare professionals.

Building a dedicated POCT team in Taiwan

At Far Eastern Memorial Hospital (FEMH), a large private hospital in Taiwan, different hospital departments used to manage POCT without any centralised oversight. This put unnecessary strain on busy physicians, nurses and hospital staff and led to various operational challenges, according to Dr Fang Yeh Chu, Director in the Department of Clinical Pathology and QMC at FEMH.

Dr Chu convened a task force to examine the issue, and after a half a year of evaluation, he decided to set up a dedicated team to ensure effective implementation and regular quality control of the hospital’s POCT. At first he faced resistance from departments that wanted to maintain the status quo, but as the benefits of this approach became increasingly clear, he soon gained the support of the broader hospital community.

“It takes time to overcome the different mindset of different employees and specialties, but through this process the quality of patient care has improved,” says Dr Chu. Looking forward, he believes that more hospitals in Taiwan and across Asia will adopt higher POCT quality targets, including through POCT-specific accreditation standards like ISO 22870, and set up dedicated POCT teams to help achieve those standards.

Improving point-of-care coordinator capacity in Vietnam

At Franco-Vietnam Hospital (FVH), a 220-bed private hub hospital in Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC), Dr Thuy Loan Chi Nguyen led the creation of FVH’s POCT programmes over the past several years. In a recent paper for Point of Care that she co-authored with Dr Gerald Kost, one of the world’s leading experts in POCT, she shares experiences and research that can support the goal of educating the next generation of point-of-care coordinators in Vietnam [1].

Dr Nguyen saw ample scope for improvement. Based on a needs assessment of 22 hospitals and 8 community medical stations in Ho Chi Minh City, as well as 16 provincial hospitals from 8 geographic regions in Vietnam, the team found that many hospitals with POCT had no laboratory oversight and performed POCT without internal or external quality control. Clinicians were poorly informed about their POCT options for urgent, emergency care and bedside contexts. In the near-total absence of point-of-care coordinators at hospitals and national guidelines on POCT usage, many key tests were either unavailable or used sub-optimally.

Despite spearheading educational and exchange initiatives to improve point-of-care coordinator capacity, Dr Nguyen notes that Vietnam continues to lag regional neighbors like Thailand and Malaysia, both of which have formal POCT guidelines [2,3]. The paper recommends further policy development in Vietnam and Southeast Asia.

POC management as a medical discipline

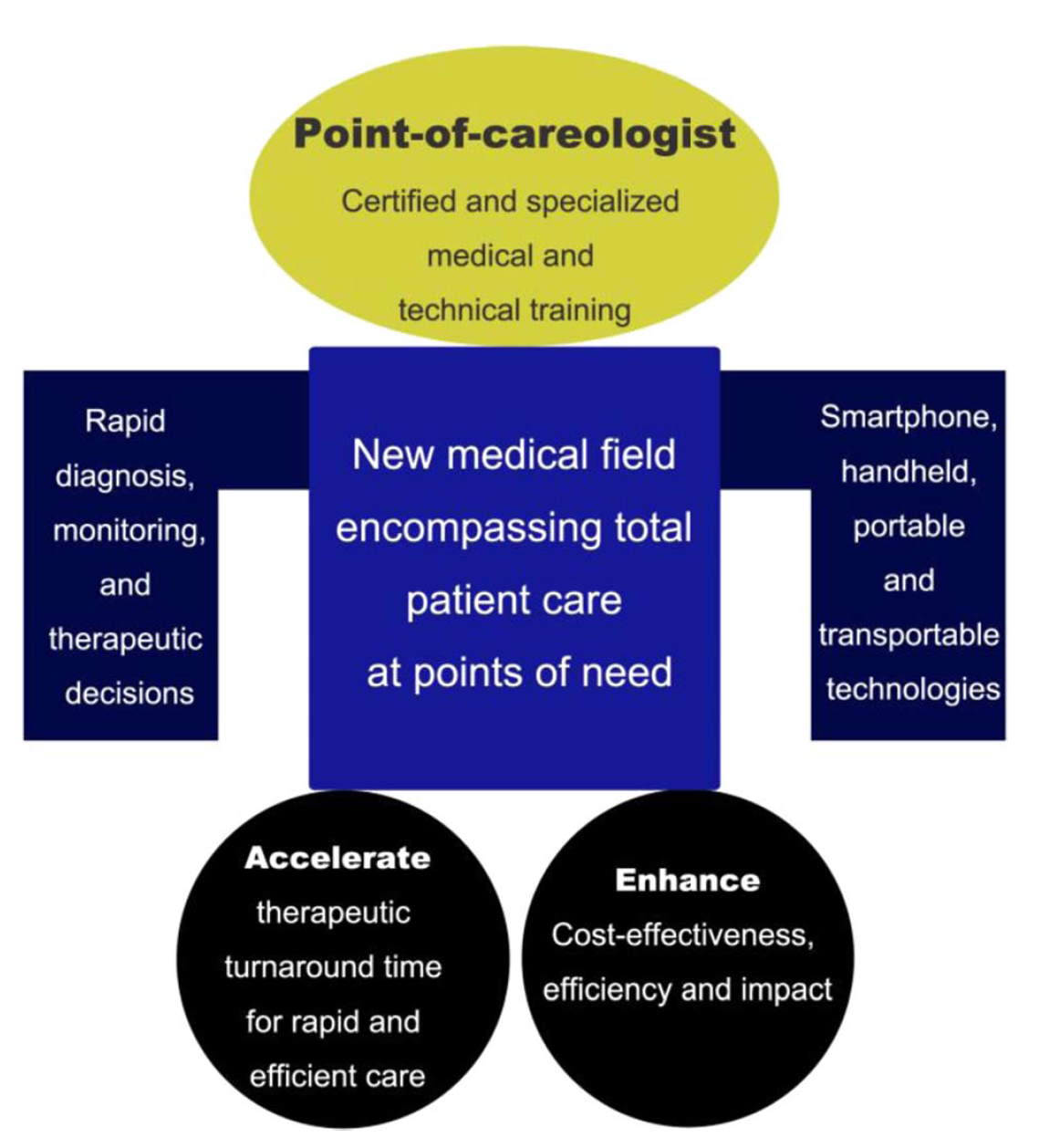

As point of care coordination gains traction as a job category, some believe the complexity and importance of POCT management necessitates the creation of an entirely new medical specialty called “point-of-careology” [4]. This specialty aims for operational excellence for the use of POCT in both clinical and community settings, as well as broader contributions to POCT research, policy and innovation.

Achieving these benefits will require more scientific research and innovation, including partnerships with IVD developers and manufacturers. As many types of diagnostic testing become increasingly distributed and predictive, POCT professionals have vast opportunities to help shape the future of care.

References:

[1] Nguyen C, Kost GJ. “The Status of Point-of-Care Testing and Coordinators in Vietnam: Needs Assessment, Technologies, Education, Exchange, and Future Mission.” Point of Care (2020) 19.1:19-24. doi: https://10.1097/POC.0000000000000196

[2] The Point of Care Testing Steering Committee. National Point of Care Testing Policy and Guidelines. Putrajaya, Malaysia: Ministry of Health Malaysia Medical Development Division. July 2012. Available at: http://moh.gov.my/images/gallery/Garispanduan/National_Point_of_Care_Testing.pdf. Accessed 17 Sept 2020.

[3] Ministry of Public Health. Thailand’s National Guidelines for Point-of-care Testing (POCT). Bangkok, Thailand: MOPH; 2015. Available at: http://blqs.dmsc.moph.go.th/assets/Userfile/POCTguideline.pdf. Accessed 17 Sept 2020.

[4] Liu X, Zhu X, Kost GJ et al. “The creation of point-of-careology.” Point of Care (2020) 18.3: 77-84. [open access] doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/POC.0000000000000191

[5] Kost GJ. “Designing and Interpreting COVID-19 Diagnostics: Mathematics, Visual Logistics, and Low Prevalence.” Acrh Pathol Lab Med (2020) doi: https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2020-0443-SA