Japan is a global leader in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) surveillance, with an effective programme that enables early-stage carcinomas detection leading to positive patient outcomes (62% of HCC patients are diagnosed at stage A and B [1] leading to 5-year overall survival rates as high as 44%). Japan’s medical care, health policy and health insurance offerings are also world class, yet unmet needs continue to affect the management of HCC, from detection and diagnostics to daily clinical practice.

To learn more about Japan’s progress and challenges in HCC management, Lab Insights spoke with Dr Shun Kaneko, a hepatologist whose clinical research focuses on viral hepatitis, risk analysis for HCC development and liver cancer treatments. Dr Kaneko’s ultimate goal is to eradicate liver cancer by not only achieving effective anti-cancer treatments, but also identifying and suppressing risk factors for liver carcinogenesis from chronic liver disease.

Epidemiology and treatment of HCC in Japan

In recent years, the epidemiology of liver cancer in Japan has changed with the implementation of screening for hepatitis B and C virus (HBV and HCV) infections and HBV vaccinations. While HCV-related HCC has decreased, and non-B and non-C (NBNC) liver disease is increasing, notes Dr Kaneko.

Advanced HCC remains a problem, with many cases remaining undiagnosed due to its asymptomatic nature or to patients avoiding screening. Also, while some viral hepatitis patients benefit from treatment with direct-acting antiviral (DAA) agents or nucleic acid analogues, NBNC patients like those with alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease have fewer treatment paths. Furthermore, occupational and health screenings for viral hepatitis still miss some patients, even those who are positive for hepatitis and who need more detailed testing.

On the plus side, Japan’s healthcare scheme provides financial support for many diagnostic and treatment procedures, including combination therapies and expensive therapies such as DAA. With an increase in the availability of novel therapeutic agents, more HCC patients can now be treated. While atezolizumab and bevacizumab now join as effective, first-line treatments for HCC, however, Japanese patients with poor hepatic reserves or highly advanced liver cancers face a poor prognosis, regardless of treatment advances and availability.

Diagnostic and surveillance protocols

For ‘high-risk’ patients—including those with chronic hepatitis B, chronic hepatitis C, or cirrhosis—the Japanese Society of Hepatology’s Guidelines for Liver Cancer Examination and Treatment recommends ultrasonography every 6 months and tumour marker evaluation [2]. For ‘ultra-high risk’ patients with HBV and HCV cirrhosis, the society recommends more frequent ultrasonography every 3-4 months, tumour marker (AFP, AFP-L3, PIVKA) assays and optional dynamic CT/MRI scans every 6-12 months.

For younger and healthier Japanese, the country’s surveillance system applies a risk stratification strategy with a preceding evaluation by a doctor that is followed by the use of diagnostic tools relevant to a patient’s age and prior history of health checks. Young patients may have a viral hepatitis background but are asymptomatic and have not had prior health screening. To ensure that these individuals are not missed, there are efforts to screen them in the workplace and to use more advanced surveillance tools to capture this population completely and quickly.

Japan’s surveillance efforts are also supplemented by social and media initiatives, including television programmes or campaigns on viral hepatitis and HCC. “At our institution, patients and the public are educated on asymptomatic disease and fatty liver as a risk of liver cancer, disease monitoring by imaging is offered for advanced fibrosis, workshops are run not only for patients but also general paractioners who need detailed examinations, and research is also conducted on medical health check data,” notes Dr Kaneko.

Areas of unmet need and hopes for the future

Despite being a global leader in HCC surveillance, Dr Kaneko acknowledges that Japan has many areas for improvement. “Japan’s cancer screening system is satisfactory, but difficulties in following up with patients persist,” he notes. “Stomach or colon cancer patients are monitored for five years after surgery, and no longer if there are no recurrences. But for HCC patients, it is difficult to know when to end follow-up.”

Capturing more patients will require new technologies, including novel biomarkers and diagnostic tools, because AFP, a mainstay of diagnostic markers for HCC alongside PIVKA and other AFP isoforms, is not always accurate, sensitive or indicative of disease. Doctors currently rely on established biomarkers in routine clinical practice, patient screening or surveillance, and await genomic biomarkers that can facilitate precision medicine.

For his own clinical practice, Dr Kaneko wants a diagnostic tool that can assess individual differences, prognosis, and carcinogenicity, and that can select appropriate therapeutic agents. Beside genomic and precision medicine, he hopes to see progress on novel HBV markers, new therapeutic agents, and tests to distinguish non-alcoholic steatohepatitis from simple steatosis.

Dr Kaneko also notes that evolving government policies will be critical for improving the quality of screening and care for liver cancer. “Policymakers should know that proper screening allows early detection and early treatment and improves prognosis, but there must be realistic limits to costs,” notes Dr Kaneko.

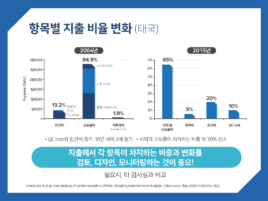

Countries looking at Japan’s successes for guidance can consider the combination of imaging with tumour marker surveillance for risk classification and implementing this in daily clinical practice. Doing so has raised the proportion of HCC in Japan that is detected early, and the proportion of patients who can receive local treatment and improved prognosis. From the viewpoint of cost effectiveness, countries with the financial resources and medical infrastructure would be wise to conduct such surveillance.

References:

[1] Kudo M. (2018). Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Japan as a World-Leading Model. Liver cancer, 7(2), 134–147. https://doi.org/10.1159/000484619

[2] Guideline on Liver Cancer Examination and Treatment. https://www.jsh.or.jp/English/examination_en/. Published 2021.