Key takeaways:

-

-

-

-

- APAC’s healthcare systems are shifting away from hospital-centric care, with both consumers and clinicians backing a move toward empowered, accessible primary care via decentralised testing.

- Point-of-care testing (POCT) is enabling this shift – bringing lab-quality diagnostics into GP clinics, family practices, pharmacies, and rural outposts across the region.

- Point of care HbA1c testing reduces patient revisits, speeds up treatment decisions, and lowers long-term costs – especially in underserved and remote communities.

- Programmes like the ACE initiative show that, with proper training and quality control, non-lab staff in rural settings can deliver accurate, high-value testing for diabetes management.

- For respiratory illnesses, POCT allows rapid triage and accurate diagnosis at the clinic level, reducing inappropriate antibiotic use and easing the burden on tertiary hospitals.

- Real-world evidence – from Vietnam to Australia and the UK – proves that POCT can reduce emergency evacuations, cut healthcare spending, and improve outcomes across diverse conditions.

- APAC’s healthcare systems are shifting away from hospital-centric care, with both consumers and clinicians backing a move toward empowered, accessible primary care via decentralised testing.

-

-

-

The shift towards decentralised healthcare in APAC

Hospitals across the Asia-Pacific region are under pressure. Tertiary care centres are stretched thin by growing patient volumes, ageing populations, and chronic disease burdens that were never meant to be managed within hospital walls. Yet today, patients still funnel into these high-cost environments for conditions that could – and should – be handled closer to home.

That shift is already underway. In countries like Australia, India, and Singapore, around 70% of consumers [1] say they trust their primary care provider to manage their overall health – a sign that the foundation for decentralised care is not only in place but ready to scale.

In Australia, the International Centre for Point-of-Care Testing (ICPOCT) [3] at Flinders University now supports 72 remote clinics. Singapore’s Healthier SG [4] programme empowers family doctors to take the lead in chronic disease management.

Healthcare delivery is moving beyond hospital walls – and physicians are on board. Over 80% of doctors in the region [1] agree that non-emergency services should shift to outpatient and primary care settings, freeing up tertiary systems for true critical care.

However, for that shift to succeed, primary care needs more than policy – it needs tools. Point-of-care testing (POCT) has emerged as one of the most powerful enablers of decentralised care. By delivering lab-quality diagnostics in minutes, POCT equips frontline providers with the speed and accuracy to triage high-risk cases, monitor chronic disease, and manage infectious outbreaks – without sending patients to overwhelmed hospitals or distant labs.

Let’s explore how POCT is reshaping the frontline of healthcare in APAC – from GPs and diabetes clinics to community pharmacies – and why it’s not just a diagnostic convenience but a strategic necessity.

Hospitals are no longer the default, and that’s a good thing

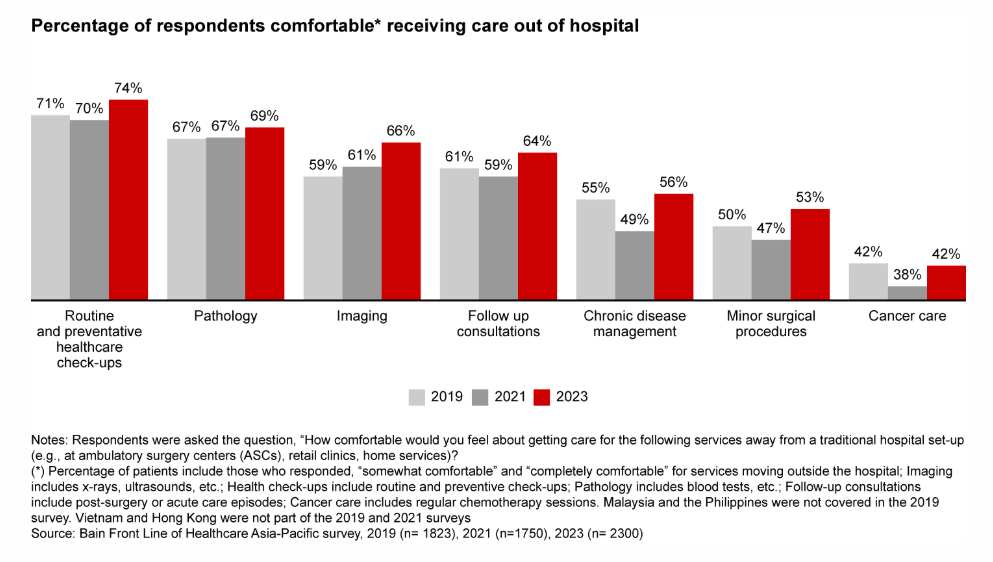

According to recent trends across APAC, the belief that hospitals are the sole default for primary care is shifting. Technology, consumer expectations, and convenience are pushing care closer to where people live and work.

Patients today want fast, affordable, and local options – and they’re increasingly comfortable getting routine check-ups and diagnostic tests outside the hospital. From pharmacies to community clinics, healthcare is showing up in more accessible places.

50% of consumers across APAC say they’re open to digital-first care models like telemedicine and remote monitoring in the next five years, and nearly 70% prefer a single, unified touchpoint for their healthcare. [1]

Can point-of-care HbA1c testing speed up care decisions for patients with diabetes?

For people managing diabetes, every extra clinic visit adds up – in time, travel, and cost.

As the burden of diabetes grows, so does the need to identify undiagnosed cases early and monitor known patients more efficiently. Equipping primary care clinics with easy-to-use POCT tools makes it possible to test patients while they’re already onsite – reducing missed opportunities and ensuring quicker care decisions without requiring additional visits.

For providers, it’s a practical solution that fits into existing workflows. For patients, it’s one less step between diagnosis and action.

Studies have shown that POCT can reduce patient revisits by up to 61%, cutting down not only on time in the waiting room but also on hidden costs like transportation, parking, and time off work. Fewer visits also mean less administrative overhead for clinics: one study found that POCT led to 89% fewer follow-up calls, 85% fewer mailed results, and a 21% drop in the number of tests per patient visit. [5]

Beyond efficiency, patient satisfaction and trust are critical for long-term engagement – especially in chronic disease management. Point-of-care testing doesn’t reduce doctor–patient interaction; it makes each visit more meaningful. When diagnosis and treatment decisions happen in the same consultation, clinicians can provide timely, confident care that builds trust from the very first visit. Patients are more likely to return when they feel seen, heard, and helped—without the burden of multiple appointments or delayed answers.

While unit costs for POCT may be higher than lab-based testing, the broader picture tells a different story. Improved glycemic control, fewer complications, and less hospital time could translate into meaningful savings – for both health systems and patients. There’s also growing confidence in the analytical accuracy of modern POCT devices. In a six-year review from Norway, up to 90% of GP clinics using POCT met quality standards comparable to hospital labs. [6]

The ACE (Analytical and Clinical Excellence) program, [7] developed in partnership with international universities, is expanding access to HbA1c and urine albumin creatinine ratio (ACR) testing through POCT in 35 rural and remote primary care services across countries including Canada, Thailand, East Timor, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, and South Africa.

Early findings revealed high rates of poor glycemic control and that around 40% of patients had signs of kidney damage (micro- or macroalbuminuria). [7] Despite being run by non-lab staff, quality assessments showed strong analytical performance across sites – proving that, with proper training and quality assurance, decentralised POCT can close serious diagnostic gaps in diabetes care.

Can early respiratory testing at the frontline improve patient outcomes?

Respiratory illnesses like influenza and RSV often lead to overcrowded hospitals, especially during seasonal peaks. Delayed diagnoses can result in inappropriate antibiotic use and insufficiently prompt triage for high-risk individuals, such as the elderly and immunocompromised.

How POCT Assists:

-

-

-

-

- Rapid Results: Flu A/B rapid antigen or molecular tests at primary clinics can deliver results within 10–15 minutes, enabling immediate clinical decisions.

- Antibiotic Stewardship: POCT helps differentiate between viral and bacterial infections, reducing unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions. [8]

- Efficient Triage: High-risk patients can be promptly identified and referred to tertiary care on the same day.

-

-

-

Implementing C-reactive protein (CRP) POCT in primary health care settings significantly reduced antibiotic prescriptions for non-severe acute respiratory infections in Vietnam. A pragmatic cluster-randomised controlled trial demonstrated that CRP POCT decreased antibiotic prescribing without compromising patient recovery. [8]

When the first wave of COVID-19 hit the UK, hospitals scrambled to manage a surge of patients with respiratory symptoms. A study put point-of-care testing to the test – using the molecular POCT panel at the bedside to diagnose suspected COVID cases.

The results were hard to ignore. Patients tested with POCT got results in just 1.7 hours, compared to over 21 hours via standard lab PCR. [9] They were also more likely to be diagnosed accurately, with 39% testing positive in the POCT group versus 28% in the lab-tested group. [9]

For frontline teams managing infectious outbreaks, faster diagnosis means faster isolation, faster decisions, and fewer bottlenecks.

Real-world impact: better outcomes, lower costs

From the Pacific to Southeast Asia, decentralised diagnostics have shown measurable health and economic benefits.

-

-

-

-

- In New Zealand, POCT improved diagnostic accuracy in rural hospitals by 43%, reducing transfers and increasing safe discharges. [10]

- POCT helped prevent 30% of emergency medical evacuations in Australia’s Northern Territory – saving an estimated AUD $21.75 million annually across conditions like chest pain, missed dialysis, and acute diarrhoea by avoiding unnecessary transfers. [11] POCT for Hepatitis C in outreach clinics cut the cost per treatment initiation by 35% compared to lab testing. [12]

- In adult patients, CRP POCT [13] has been shown to improve diagnostic accuracy for lower respiratory tract infections. A study highlighted [13] that using CRP testing in primary care settings helped differentiate between bacterial and viral infections, leading to more appropriate antibiotic prescribing and uncovering cases that might have been misdiagnosed without the test.

-

-

-

Where do decentralised diagnostics make the most impact?

Across APAC and other LMICs, POCT is being deployed in diverse clinical environments, including:

-

-

-

-

- Primary Care or GP Clinics: Often the first stop for non-emergency symptoms, primary care settings are where triage decisions happen. POCT enables same-day tests for infections, heart markers, and chronic disease indicators – speeding up decisions and reducing unnecessary hospital referrals. For example, NT-proBNP testing at the point of care can help identify patients at risk of heart failure. A primary care physician can perform the test in-clinic and immediately triage patients who require urgent hospital care, avoiding dangerous delays. Similarly, troponin tests can help rule out cardiac events at the clinic itself.

- Family Medicine Clinics: These settings manage patients with multiple comorbidities – where risk stratification is key. POCT enables immediate testing for HbA1c, lipids, or D-dimer, [15] allowing clinicians to adjust care plans in real-time.

- Diabetes Clinics: POCT often streamlines diabetes monitoring by enabling diagnosis and treatment adjustments to happen in the same visit. This reduces the number of follow-up appointments and cuts down the effort required from patients and caregivers – especially in settings where returning to the clinic involves travel, lost income, or time off work. On-the-spot HbA1c testing supports quicker decision-making, better glycaemic control, and more convenient chronic disease management.

- Pharmacies and Drug Shops: In many parts of Asia, pharmacies are the first – and sometimes only – point of contact for healthcare. POCT enables these settings to offer credible health screening for flu, COVID, and chronic conditions using simple finger-prick tests or nasal swabs administered by a healthcare professional – without the need for additional trips to labs or clinics.

-

-

-

Looking ahead

As APAC’s healthcare systems brace for growing demand, decentralised diagnostics will define the difference between reactive and resilient care.

The tools are here. The momentum is building. Now, it’s about bold implementation – putting fast, accurate testing where it matters most. With the right investments, partnerships, and policy backing, primary care can become the most potent engine of equitable, efficient healthcare in the region.

Because better outcomes don’t start at the hospital – they start at the frontline. And the future of diagnostics is already there, waiting to be scaled.

References:

[1] Bain & Company. 2020. “Asia-Pacific Front Line of Healthcare Report 2020.” Bain & Company

[2] Bain & Company. 2024. “Asia-Pacific Front Line of Healthcare 2024.” Bain & Company. Accessed April 22, 2025. https://www.bain.com/insights/asia-pacific-front-line-of-healthcare-2024/.

[3] Shephard, Mark, Anne Shephard, Susan Matthews, and Kelly Andrewartha. 2020. “The Benefits and Challenges of Point-of-Care Testing in Rural and Remote Primary Care Settings in Australia.” Arch Pathol Lab Med 144 (11): 1372–1380. doi:https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2020-0105-RA.

[4] Ministry of Health Singapore. 2022. White Paper on Healthier SG. White Paper, Government of Singapore.

[5] Crocker, Benjamin J, Elizabeth Lee-Lewandrowski , Nicole Lewandrowski, Jason Baron, Kimberly Gregory , and Kent Lewandrowski. 2014. “Implementation of point-of-care testing in an ambulatory practice of an academic medical center.” American Journal of Clinical Pathology 142 (5): 640–646. Accessed 2025. doi: 10.1309/AJCPYK1KV2KBCDDL.

[6] Schnell, Oliver, Benjamin Crocker, and Jianping Weng. 2016. “Impact of HbA1c Testing at Point of Care on Diabetes Management.” Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology 11 (3): 611. doi:10.1177/1932296816678263.

[7] Motta, Lara A, and Mark Shephard. 2015. “The International Analytical and Clinical Excellence Program.” Point of Care: The Journal of Near-Patient Testing & Technology 14 (3): 76-80. Accessed 2025. doi:10.1097/POC.0000000000000053.

[8] Staiano, Annamaria, Lars Bjerrum, Carl Llor, Hasse Melbye, Rogier Hopstaken, Ivan Gentile, Andreas Plate, Oliver van Hecke, and Jan Y Verbakel. 2023. “C-reactive protein point-of-care testing and complementary strategies to improve antibiotic stewardship in children with acute respiratory infections in primary care.” Frontiers in Pediatrics 11: 1221007. Accessed 2025. doi:10.3389/fped.2023.1221007.

[9] Brendish, Nathan J, Stephen Poole , Vasanth V Naidu, Christopher T Mansbridge, Nicholas J Norton, and Helen Wheeler. 2020. “Clinical impact of molecular point-of-care testing for suspected COVID-19 in hospital (COV-19POC): a prospective, interventional, non-randomised, controlled study.” The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 8 (12): 1192-1200. Accessed 2025. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30454-9.

[10] Blattner, Katharina, Garry Nixon, Susan Dovey, Chrystal Jaye, and John Wigglesworth. 2010. “Changes in clinical practice and patient disposition following the introduction of point-of-care testing in a rural hospital.” Health Policy 96 (1): 7-12. Accessed 2025. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.12.002.

[11] Spaeth, Brooke A, Billingsley Kaambwa, Mark DS Shephard, and Rodney Omond. 2018. “Economic evaluation of point-of-care testing in the remote primary health care setting of Australia’s Northern Territory.” ClinicoEconomics and Outcomes Research: CEOR 2018 (10): 269-277. Accessed 2025. doi:10.2147/CEOR.S160291.

[12] Shih, Sophy T.F., Qinglu Cheng, Joanne Carson, Heather Valerio, Yumi Sheehan, and Richard T Gray. 2023. “Optimizing point-of-care testing strategies for diagnosis and treatment of hepatitis C virus infection in Australia: a model-based cost-effectiveness analysis.” The Lancet Regional Health: Western Pacific 36: 100750. Accessed 2025. doi:10.1016/j.lanwpc.2023.100750.

[13] Llor, Carl, Andreas Plate, Lars Bjerrum, and Ivan Gentile. 2024. “C-reactive protein point-of-care testing in primary care—broader implementation needed to combat antimicrobial resistance.” Frontiers in Public Health 12: 1397096. Accessed 2025. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2024.1397096.

[14] Van Hecke, Oliver, Lars Bjerrum, Ivan Gentile, Rogier Hopstaken, Hasse Melbye, Andreas Plate, Jan Y Verbakel, Carl Llor, and Annamaria Staiano. 2023. “Guidance on C-reactive protein point-of-care testing and complementary strategies to improve antibiotic prescribing for adults with lower respiratory tract infections in primary care.” Frontiers in Medicine 10 (2023): 1166742. Accessed 2025. doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1166742.

[15] Schols, Angel M.R., Eline Meijs, Geert-Jan Dinant, Henri E. J. H. Stoffers, Marielle M.E. Krekels, and Jochen W. L. Cals. 2019. “General practitioner use of D-dimer in suspected venous thromboembolism: historical cohort study in one geographical region in the Netherlands.” BMJ Open 9 (5): e026846. Accessed 2025. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026846.